Two Practical Ways to Integrate Behavioral Finance in Your Practice

Every advisor would like to snap their fingers and have their clients behave like more rational, patient investors. While the idea that clients are prone to bad investing behavior is not new, one of the primary challenges for financial advisors – and one of the greatest values they provide – is practically applying behavioral finance concepts for the benefit of their clients.

1. Show (Don’t Tell) Clients When They’re Wrong

Overreaction and availability bias are the tendency to overreact to recent news, and to more heavily weight decisions toward recent information. As legendary investor Sir John Templeton said, “The four most dangerous words in investing are, it’s different this time.”

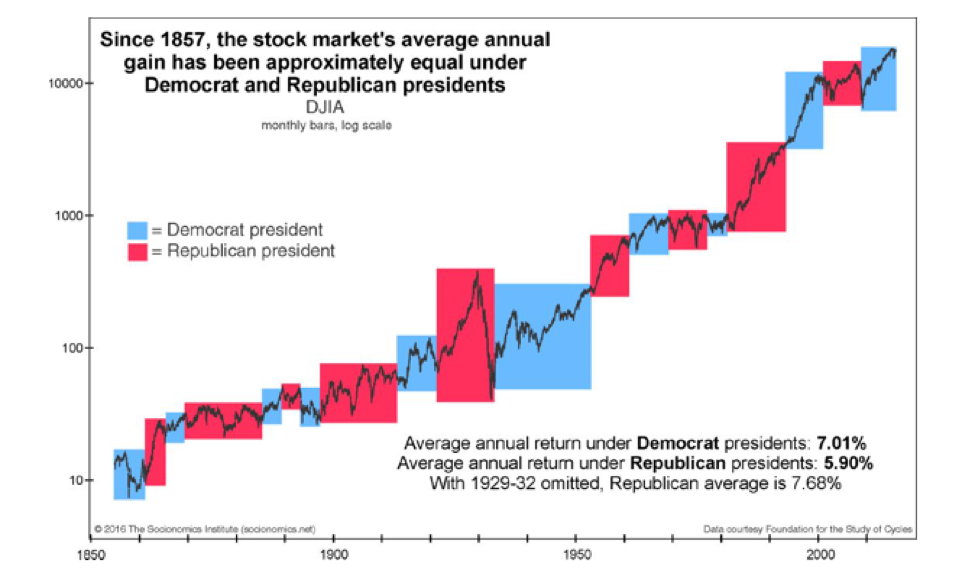

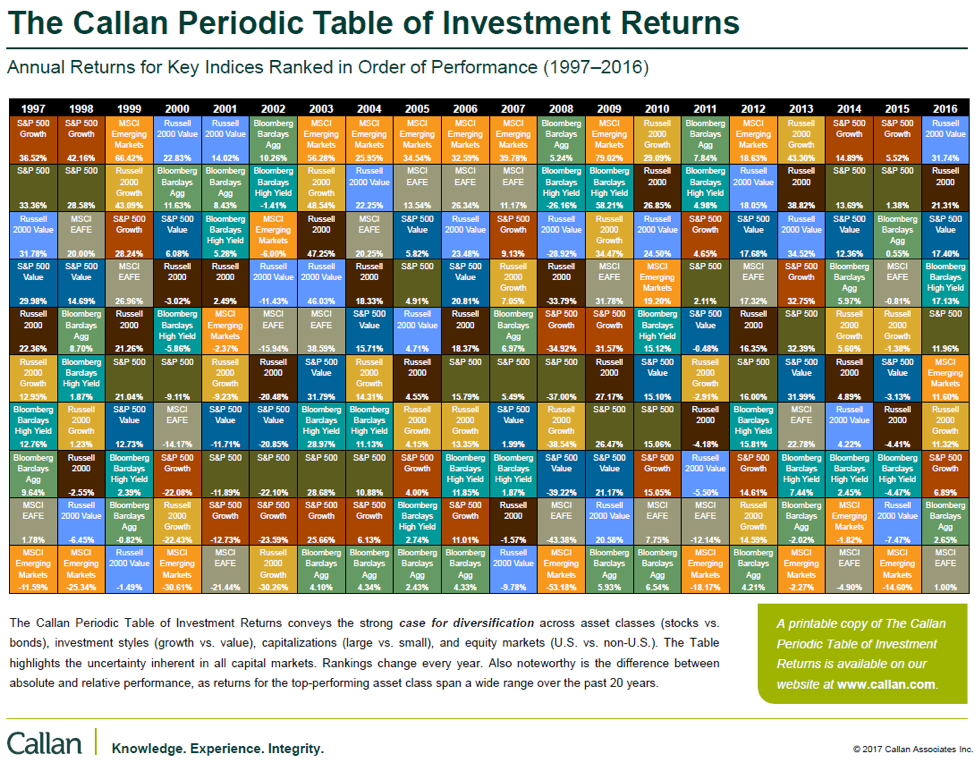

Taking an advisor’s word that ‘everything will be OK’ may not be enough for clients panicking from bad news. Charts, graphs, and visual illustrations can be the best way to hammer home that this time isn’t different after all. They take concepts that are vague and difficult to grasp and make them tangible and easier to internalize.

This one, showing the growth of the DJIA through Democrat and Republican presidents, is helpful ammunition for combating emotional reactions to political shifts (Source: The Socionomics Institute and ElliotWave International).

The Callan Periodic Table of Investment Returns (available at www.callan.com) is also one of my favorite tools for demonstrating the importance of diversification and the unpredictability of asset class returns.

2. Put it in Writing

Client behavioral tendencies, from overconfidence to anchoring, are emotional and subconscious reactions. Their greatest threat is that we as investors do not realize that we are falling prey. This is what Robert P. Seawright calls the bias blind spot (See: Top Ten Ways to Deal with Behavioral Biases).

Seawright’s advice it to put accountability mechanisms in place. When writing an investment policy statement or conducting review meetings be specific, even exhaustive, about what the plan will be in anticipation of future situations. You can also outline the behaviors that the client is likely to experience in writing.

Research finds that in many cases acknowledging a behavioral bias ahead of time is enough to diminish its effect. Additionally, having a written record will create an accountability mechanism for the client. It sounds simple, but a client will have less skepticism about an advisor’s advice if the advisor sets expectations early and can show that they anticipated both the possible investment situation and the behavior it might cause.

Like Sisyphus rolling his boulder endlessly uphill, fighting behavioral biases is a never-ending task. Hopefully these ideas can help keep clients rolling in the right direction.